In 1974, an enormous ship sailed into the waters northeast of Hawaii. The vessel, built by billionaire Howard Hughes, was set to begin mining mineral deposits in the deep sea — or so the world believed. The deep-sea mining venture was actually a cover story for a clandestine CIA mission to salvage a sunken Soviet nuclear submarine.

Now, more than 40 years later, we’re ready to start deep-sea mining for real. We’re depleting many of our land-based stores of minerals, and remote though it is, the bottom of the ocean is a likelier source of precious minerals than asteroids. It is strewn with deposits rich in gold, copper, manganese, cobalt, and other resources that supply our electronics, green technology, and other vital tools like medical imaging machines.

In 2019, Canadian mining firm Nautilus Minerals will send robots to excavate deposits rich in copper and gold within the jurisdiction of Papua New Guinea. Other nations are hot on their heels. The International Seabed Authority, which regulates deep-sea mining in international waters, has granted contracts to more than 25 countries to explore for minerals.

“There’s…a gold rush mentality that has emerged,” says Mark Hannington, a geologist at GEOMAR-Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany. He and several other researchers gathered to discuss the prospects and risks of mining the seafloor at the American Academy for the Advancement of Sciences 2017 annual meeting in Boston.

Since no one has tried mining the seafloor yet, much remains uncertain about how it will work — or how much it will disturb the creatures that make their homes at the bottom of the ocean, even as it provides the minerals we need for more eco-friendly technology.

A Tempting Reserve

Ocean mining isn’t a new idea; diamonds have been mined from the shallow waters off southern Africa for decades. And we’ve known there were caches of minerals in the deep sea since the landmark Challenger expedition discovered the “peculiar black oval bodies” of so-called polymetallic nodules in the 1870s.

But only now are we ready to start mining them. “The challenges of exploiting a mineral resource at 4,000 plus meters has put people off until now,” says Daniel Jones, a marine biologist at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, United Kingdom.

Related: Space Mining: The Intergalactic Gold Rush is On

We may not be able to keep up with the need for scarce materials without turning to the sea. “We now have an increasing demand for metals that are becoming more expensive to acquire on land,” Hannington says.

These days, land-based miners are heading deeper and deeper into the earth for lower grade mineral deposits, says James Hein, a geologist with the United States Geological Survey. In many cases, “The really rich, high-grade deposits on land have already been mined,” he says.

It’s unlikely we’ll completely replace land-based mines by plumbing the deep sea. However, the deposits in the ocean are vast and sit right on the seafloor. "There’s tremendous amounts of metal," Hein says. "The question is how much of it’s going to be economically extractable."

Some of the mining will be needed to improve the standard of living in developing countries like China, India, Indonesia, and Brazil, but Hein says is going to require an "unbelievable amount" of minerals.

These deposits will also play a valuable role in green industries.

"Wind turbines and electric cars and hybrid cars and solar cells and all these things are requiring the mining of vast new quantities of rare metals," Hein says. “These are also abundant in deep ocean mineral deposits.”

Minerals Within Reach

Deep below the ocean’s surface, precious minerals have spent millions of years building up on rocks and soft sediments. The deposits being eyed by deep-sea prospectors come in three main flavors.

The deepest, called polymetallic nodules, are found up to 6,000 meters below the surface. These form when metals slowly collect on debris such as shark teeth and fossils lying in the sediment. Nodules can grow from golf ball-sized nuggets up to the size of footballs, and are rich in metals including nickel, copper, cobalt, and lithium (which is used in batteries).

It shouldn’t be difficult for robots to scoop up these loose, knobby lumps. “They’re enormously abundant and they’re easy to recover,” Hannington says. “The challenge…that many companies are working on is how to lift the nodules to the sea surface.” T

ools such as long pipes equipped with pumps may ferry the minerals to waiting ships.

If polymetallic nodules can be successfully mined, “We could satisfy global demand for nickel and cobalt and maybe even copper for a very long time,” Hannington says.

When metals seep out of the seawater onto rocks, they form pavement-like surfaces called ferromanganese crusts. These are especially plentiful in cobalt and rare elements like tellurium, which is used to make solar cells.

However, crusts will be the most challenging type of deposit to mine. They must be separated from the rocks they are growing on, which would dilute the ore and make it less valuable. “We haven’t quite figured out how to get them off," Hannington says, "and I think that could be some ways down the road."

Related: Why NASA Wants to Send a Submarine to Titan

Minerals also concentrate in so-called seafloor massive sulfides, which form around hydrothermal vents. In these areas, superhot fluid spews up from the Earth’s crust and drops minerals into the surrounding water.

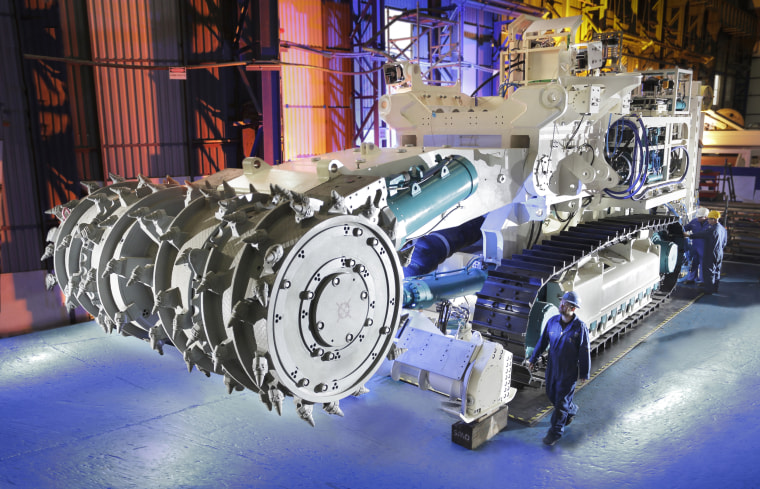

Seafloor massive sulfides are rich in metals such as copper, gold, silver, and zinc. It's this kind of trove that Nautilus Minerals plans to excavate. The company will send robots weighing hundreds of tons to crawl over the seafloor on treads, chewing up the hard deposits and slurping up the pulverized slurry so it can be carried to the surface.

Any deep-sea mining venture will have to contend with punishing conditions; the pressure is immense on the ocean’s floor, and temperatures are frigid. "Companies…have to have these machines operating nearly year-round, and will that be possible?” Hein says. “That is such a great unknown.”

Striking a Balance

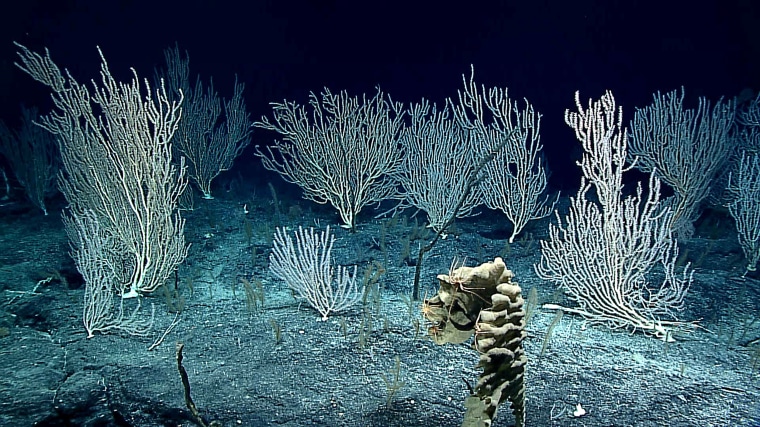

Sending machines to dig up the ocean floor will have consequences for its delicate ecosystems. Many deep-sea creatures are accustomed to conditions that, while extreme, don’t change much over time. “They’re particularly sensitive to any disturbance,” Jones says. “It’s likely that they’ll take a very long time to recover.”

Some animals rely on the nodules themselves. Mining could obliterate their habitat, removing homes that take millions of years to grow. And machines might alter the sediments that other animals dwell in. “They’ll remove the surface layer which has got a lot of the food in it,” Jones says.

Mining will also kick up plumes of sediment that could blanket or bury animals. The plumes might also release toxic metals such as lead.

One way to protect sensitive habitats is to set aside networks of protected areas. Mining could be carried out in patterns that leave space for larvae from other areas to come in and recolonize, and the still-active hydrothermal vents that are colonized by vibrant communities of tubeworms and other animals could be avoided in favor of dead ones.

Nautilus Minerals is considering strategies to lessen the damage from deep-sea mining, such as moving animals to safety or planting crates to give displaced creatures an alternative home.

Figuring out what kinds of impacts deep-sea mining will have could help guide people deciding where to mine and what regulations should govern mineral extraction. Researchers are investigating how experiments that simulate deep-sea mining affect the surrounding ecosystems. Jones and his colleagues recently reported that most of the areas considered have fewer animals and species than untouched land, even decades later.

Related: The Future of Earth's Shifting Continents Might Surprise You

It might not be easy to balance deep-sea mining with conserving pristine environments. However, demand for the minerals that bolster our civilization will only increase.

“By 2050 we’re going to have another couple billion people on the planet, and they [will] all want refrigerators and television sets,” Hannington says. “The materials for that are going to have to come from someplace.”

Other questions remain. It’s not clear yet how much deep-sea mining will cost. We’ve still explored only a tiny fraction of the ocean’s floor, and don’t really know what amounts of minerals can be extracted from it.

We also have a lot to learn about how its inhabitants might contribute to our own wellbeing. Habitats that occur at relatively shallow depths, like ferromanganese-crusted seamounts, may shelter creatures that feed commercially valuable fish, says Stace Beaulieu, a biological oceanographer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Masschusetts, who also spoke at the AAAS session. And deep-sea animals and microbes could be a source of compounds that may be used in new medicines.

“You can’t have a mining event that doesn’t have any impacts,” Jones says. “The more important question is, can you have mining that doesn’t have a really, really major impact? We may be able to do that, but we don’t know the answer yet.”